Robert Devaney

September 6, 2012

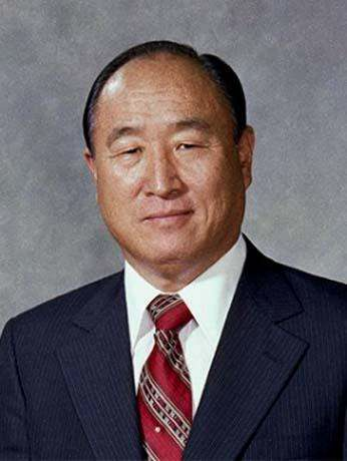

The Rev. Sun Myung Moon, Korean religious leader, businessman and founder of the Unification Church died Sept. 3 in South Korea. He was 92. Moon considered himself the second coming of Jesus Christ, an idea directly heretical to mainstream Christianity.

In the popular mind, his Unification Church provoked images of mass marriages performed by Moon and his wife -- the "True Parents" -- and of young promoters who sold flowers at the airport or on the streets. And his Moonies, a word church members do not like, have been accused of being part of a religious cult.

His attendant business interests ranged widely from media and automobiles to supplying fresh fish to local restaurants, namely, sushi.

But the powerful ambitions and personality of Moon sought more: he wanted influence throughout the world, East to West. Where was the best place to set up his own version of a heaven-on-earth lobbying firm? In America. And the best place there? Of course, the nation's capital, Washington, D.C.

Beside his religious activities, the fiercely anti-communist Moon become known in the United States for strongly supporting then-enbattled President Richard Nixon, who later resigned. He led a huge rally at the National Mall, complete with fireworks, in the late 1970s. People here took notice, even as a few young Unification Church missionaries spoke casually with Georgetown University students in the lobby of Lauinger Library. (A new religion which unites the peoples and churches of Christianity can sound fresh, pure and worthy to a young mind.)

Moon's church and businesses continued to grow, and he was ready to stake his claim as a major Washington influencer by establishing the Washington Times in 1982. While it was during the administration of President Ronald Reagan, it came along before many other popular media outlets which trumpeted conservative issues.

I got the opportunity to work as an editor at the Washington Times during the 1990s -- the Bill Clinton years -- working in special sections. We wrote and edited varied features, anything from travel, history, dining, real estate, jobs to specials on inaugurations, Martin Luther King, Jr., Apollo XI and World War II. Our bailiwick did not involve any ideological comments, specifically speaking, although we were aware of the preferences of the editor at the time, Wesley Pruden. Just being in the newsroom, it was instructive for a centrist Democrat like myself to learn a bit of the thinking from the conservative -- and increasingly Republican -- playbook.

Now, the Washington Times newsroom is off the beaten path, as far as media offices go. While the Washington Post -- and the Washington Star (many staffers went to the Times when it folded) in its heyday -- chose downtown D.C., the Times is in Northeast D.C. on New York Avenue between the National Arboretum and the train tracks.

There was that one day in the mid-90s when Rev. Moon, who would visit occasionally and go straight to the executive offices, walked around the voluminous newsroom meeting each editor and writer individually at his or her desk. One veteran writer, surprised at this never-before greeting, said that it was either really bad or really good. (The Times could wait for about another 15 years before things might go really bad.) Moon smiled as he joked about a top investigative reporter's weight and poked him in the belly, saying he liked to eat as much fish as Moon liked to. At least, that's what what the translator told the reporter who was not used to being messed with and who, I imagined, had to restrain himself as I also imagined steam coming out of his ears.

Like most newsroom creatures, Times employees were skeptical of authority and would make a quip as easily as those on 15th Street. They called their paper "little scrappy," which did more with less and whose editors encouraged new hires to take chances. One said he was glad people believed in God, because he knew along with others that companies affiliated with the Unification Church had worked with News World Communications to spend more $1 billion over the years on the newspaper, which was one of the first to report regularly on religion, spirituality and, yes, God.

Of course, that other newspaper on 15th Street -- "the OP" as Times editors said -- looked down at Moon's creation as Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee vowed never to visit -- until a birthday party for Arnaud de Borchgrave, a former editor-in-chief of the Times. Bradlee had worked with de Borchgrave at Newsweek in Europe and was happy to go to the New York Avenue newsroom as the Times printing presses produced a Times parody version for de Borchgrave's party in the Arbor Ballroom; the banner headline aptly read: "A legend in his own mind."

The Washington Times persevered in its quest to bring an alternative voice to the Washington and national scene, even as it sometimes beat the Post on local news stories. It was not afraid to make mistakes and offered many reporters who went on to bigger media groups a great start. Allow me to mention a few (mostly former) staffers who made the newspaper shine and had an impact for me, professionally and personally: Patrick Butters, Peter VanDevanter, Kevin Chaffee, Ann Geracimos, Tracy Woodward, Jim Brantley, John McCaslin, Lorraine Woellert, Tony Blankley, Adrienne Washington, Cathryn Donohoe, Thom Loverro, Susan Ferrechio and Jerry Seper.

After the Times fell victim to squabbles within the Moon family, its staff and sections were cut a few years ago -- and it looked like the end was near. But Moon did not want to lose face, as it were, and intervened two years ago and took the newspaper away from one of his sons who had controlled it. Today, the Times remains a strong conservative and journalistic voice amid the newer ones, such as the Washington Examiner, adding to a more dynamic media landscape. It is trying for a comeback. Whatever your opinion of its ideological bent, you know the Times kept D.C. from being a one-newspaper town. And you can thank its writers, editors, photographers, artists and pressmen -- and a self-proclaimed messiah -- for that bit of journalistic luck