In Jin Moon

September 25, 2010

WFWP 18th National Assembly

Thank you, and good morning. Welcome to the 18th National Assembly of the Women's Federation for World Peace, talking, discussing, and pondering about the dignity of women. It's truly my honor to be with all of you here this morning.

Last night I arrived from Las Vegas after spending a couple of days with my parents, who had just arrived from Korea. On the flight back I was seated next to a very interesting person, and we started talking about the Women's Federation event that I would be attending. This person asked me, "Nowadays we have a lot of different women's organizations doing a lot of great work. But tell me if you can do something about creating ideal men for all of us." (Laughter)

I said, "I'd be very happy and honored to do my part in inspiring the delegates that will be attending the conference to work together to create a lot of ideal men all around the world." I went on to tell this person, "You know, God did promise all of us women ideal men, and he told us that he placed these special ideal men in four corners of the world. Unfortunately the women found out that the world was round. So the adventure and the treasure hunt continues."

I was thinking about creating an ideal world, having and experiencing ideal men, and becoming divine and worthy women, mothers and sisters. How do we reclaim dignity? I was thinking about the word dignity, which comes from the Latin dignus, meaning "worth." We don't have to look far, but if we peruse different books written about the great women of history, or the history of women in the context of religious life, we realize that these women had to fight very hard to reclaim their dignity.

When I think about my own life as a daughter of the man we call Reverend Moon and about my own journey of self-discovery as a woman who sees herself as a divine being with a divine purpose and as someone who wishes, hopes, and aspires to be that compassionate leader that we all know we are, then I find myself meditating on the word dignity.

Many great women have come before us -- like Catherine Booth, mother of the Salvation Army, or Rosa Parks, who ignited the spirit of the civil rights movement, made great strides in the name of civil rights, and gave women of color a sense of dignity and worth in this great country of America. When we think about these women, we realize that to reclaim their dignity and worth, they had to dig in a soil that was not fertile but rather was unkind and quite hostile to them. Nevertheless, they worked and gave it their best; they gave their lives to reclaim their dignity.

But if we think about where our true dignity comes from, we must realize that regardless of what kind of cultural, racial, or economic background we come from, true dignity comes from God, our Heavenly Parent. The understanding of who we are as a worthy mother and a sister comes from understanding that God is our common Heavenly Parent and we stand as eternal daughters of God.

If we can agree that our true worth or dignity comes from God, then we can realize as women how important the concept of True Parents is. My father teaches what we must do in order to restore the difficulties of human history, or the human Fall, for which women have been accused of a lot of bad things and have been called the "whore" and the "temptress who led Adam astray." This understanding that women were the instigators of something that was horrible has been in the minds of men and women alike throughout history.

The great thing about the concept of True Parents is that through understanding ourselves as the children of God, our Heavenly Parent, we come to realize our own worth. If my father can overcome his individual difficulties and in the position of perfected Adam welcome a wonderful woman in the position of perfected Eve and stand together with her as the True Parents of humankind, they can restore and indemnify all that has gone awry in history, including the misconceptions women have had to bear for centuries.

In the understanding that men and women are divine beings and eternal sons and daughters of God who come together in the beautiful Holy Blessing, we realize that women no longer need to be bound by the concept of being the one who led Adam astray. Instead, the woman becomes the Eve that makes Adam complete in the beautiful package called the True Parents.

When we look at the ills of society, we see the hatred, hurt, and suffering caused by so much misunderstanding. Many have said that we need to make sure that women are not educated, that women are controlled, and that women stay in their proper place. Women have been seen almost like a radioactive substance that, left on its own, can do a lot of damage. But if we can understand women as divine beings who were meant to be beautiful partners to a representative person like True Father in the context of True Parents, then we realize that women are an integral part of something that makes the world beautiful.

When my father and mother go around the world teaching and sharing the message of true love and sharing about the importance of building beautiful families as the cornerstone of the society, nation, and world, it is clear that women have a very important role to play. We must have a voice, a presence in different areas of life, not just in the context of a family but in the context of a society, and in politics, religion, and economics as well. Women have been especially prepared to usher in the new millennium. We are the ones who have the responsibility of helping our brothers and fathers to be compassionate fathers, brothers, and leaders who can work together with us to bring about a world of peace.

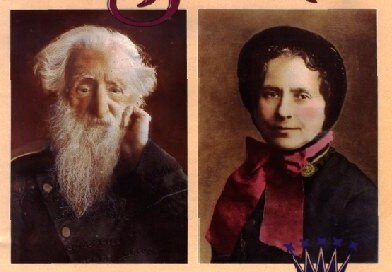

Catherine and William Booth founders of the Salvation Army

When we meditate on the concept of peace, we need to realize that if we're going to build an ideal world free from violence and hatred, we have to start with ourselves. We have to decide to be the agent of change like Catherine Booth or Rosa Parks. We have to realize that it's within our power to raise the Generation of Peace.

Rosa and Raymond Parks Civil Rights Heros

What is the Generation of Peace? I make it very simple for my children to see how I understand peace -- by taking the word and seeing it as an acronym. P stands for Heavenly Parent. We need to have an understanding that God is our Heavenly Parent. No matter how different we are, no matter where we come from, we come from the same original source.

Then we need to understand when we look at the letter E that we are Eternal sons and daughters of God; we are divine beings with a rich reservoir of true love that we need to share with the world. As eternal sons and daughters, we were born with a purpose. We were born to fulfill the special personal destiny that each of us has, men and women, male and female alike.

Looking at the letter A, we realize that we have a duty and responsibility to live our lives Altruistically, meaning living for the sake of others -- not because we're seeking our own individual salvation, but just because we want to be good people: We want to love; we want to inspire; and we want to empower each other to be the best that we can be.

When we look at the letter C, we understand that the next millennium, if it's going to be a millennium of peace, has got to be something different. We've seen world wars, we've seen hate that resulted in something as horrific as 9/11 on the shores of New York City. We've seen the suicide bombers, and we've seen children shoot each other and their teachers to death in their schoolrooms. The next millennium has to have leaders who understand the meaning of Compassion.

Our modernized world has become so efficient and technologically advanced that the understanding of our own dignity as an eternal son or daughter has not progressed in line with the progress of technology. Here we are, faced with technology that has brought us the Internet, Hollywood, and, for my children, video games. In the process we lost something that is very important to all of us as human beings. We forgot our spirituality. We forgot to pay attention to our emotional needs as well as our physical needs.

In this era of compassionate leadership, we must understand the importance of being kind in this cold, fragmented world. Just last Saturday there was an incident at Harvard University in which a young man decided to take his own life on the steps of Memorial Church. He was not a student at Harvard, but he wanted to shoot himself to shock his generation and particularly the students at Harvard.

Why did he choose Harvard? He understood it as the center of intellectual activity in America. He wanted to shock the people who are going to be future leaders, to tell them that something is amiss in our society's understanding of the true worth and dignity of human beings. He shot himself in broad daylight, in front of a lot of students busily moving from one class to another, and he had prepared a manifesto of 1,905 pages, what he called a treatise, on why he did what he did.

When you think about why someone would do such a thing, why someone would need to shock his nation and the world by killing himself, it's not so different from suicide bombers who do the same thing, blowing themselves up to shock the world because they want to make a statement. When you get to the basis of their thinking, it's a cry for help, a cry out to a world that needs to be more compassionate.

That's why we as women and as mothers have a duty and responsibility to help make that happen. We need to create a world where our children feel safe and valued, where they not only understand their dignity as human beings but also have a purpose in front of them when they think about and live their lives, fulfilling their personal destiny. We as women are the nurturers, the guides, the ones who empower and give our children the confidence to succeed.

Even in our title there is the word peace. It's the responsibility of those of us here to raise a generation whose members understand their worth, a generation whose purpose in life is not to shock the world by killing themselves but to become true sons and daughters who create beautiful families that are cornerstones of society and help build a beautiful nation and world. That is why women are necessary. We need to be in positions of power, as leaders in religion, politics, and economy. We need to show the world that it can be nurtured, guided, and empowered through compassionate leadership.

When we look at the last letter, E, we see that in our effort and heart as mothers we want to raise children who are Excellent not only externally, but also internally, children who are not just fantastic doctors, lawyers, and scholars, but also fantastic men and women who will become fantastic fathers and mothers and fantastic grandfathers and grandmothers. Then we can rest assured that in the future children will be brought up in good hands and will carry on in understanding that the world as one family under God.

I feel that the 18th conference, stressing the dignity of women, is an incredibly profound one. As someone who has been busy visiting Capitol Hill, seeing congressmen, congresswomen, and senators, highlighting the faith breaking taking place in Japan, I feel that we as women cannot waste another day.

Just last week I heard that another member of our faith was kidnapped, forcibly abducted, and subjected to faith breaking. For the last three decades, our church has witnessed the kidnapping of more than 4,300 of our brothers and sisters -- the majority of them over 21 years of age, old enough to choose how they want to worship God and live their life of faith.

In meeting many of them, I came to understand that, particularly for many of the women, it's not just faith breaking that is taking place. Our sisters are not just being emotionally abused; they're also being physically and sexually abused. These women and their dignity are being lost in the process. As somebody who understands not just my own worth and dignity as coming from God, I see their honor and dignity as coming from God as well.

As the international Women's Federation for World Peace, we cannot stand still while these women are being abused and denied their right to exercise freedom of religion. These Asian women have been silent for too long, not wanting to discuss the horrific things they've had to endure. We have to give them a voice to the world. I seek your help, including international help, to exert the right kind of pressure on the Japanese ambassador and the Japanese government so we can put an end to this faith breaking in Japan.

We have seen the recent chain of events surrounding the trial of a poor Iranian woman who was found to be having an adulterous relationship and the possibility of her being stoned to death. The president of Iran is in the process of changing his story because of all the international pressure and the international inquiries being made. Perhaps the woman did something wrong, but where is the man? Why is the man not being sentenced to be stoned to death?

If men and women everywhere are eternal sons and daughters, shouldn't we as loving mothers and fathers want to allow this woman a chance to redeem herself, to find herself as a woman of dignity? Shouldn't we as the Women's Federation for World Peace make a statement saying, "Enough killing; enough violence." We must protect each other. We must stand with each other. We must do the right thing and help our sisters and brothers in need.

So I ask all of you to please talk about these issues. Please share with the pertinent parties what is going on in Japan, and what our Unificationist brothers and sisters have had to bear for the last three decades. We have seen many great men and women before us. We have seen extraordinary Japanese women change their world for the better.

If each of us seated here this morning decides today to be that agent of change, can we not create a better world, sisters? Can we not inspire our children to be that Generation of Peace? Can we not guarantee our children and our grandchildren a safer world? I think we can. This is the starting point because we have to start talking about it. We have to start discussing it and together decide to do something about it.

I am truly honored that all of you have invited me to come and speak as one sister to another. We can make this world into that peaceful world that we all want if we decide today to work together. I think we all will, and I think we all can. So God bless, and thank you.

Notes:

Man Dies After Shooting Himself in Harvard Yard

Elias J. Groll and Naveen N. Srivatsa, Crimson Staff Writers

September 20, 2010

A bouquet of flowers lies on the top step of Memorial Church, marking the spot where a man fatally shot himself on Saturday morning.

A man who appeared to be unaffiliated with Harvard University died Saturday after fatally shooting himself on the top step of Memorial Church.

The Harvard University and Cambridge Police Departments, responding to a call about the shooting, discovered a body with a self-inflicted gunshot wound lying outside Memorial Church, according to a HUPD community advisory.

The incident took place around 10:50 a.m. on Saturday, according to CPD spokesman Daniel M. Riviello.

At that time, a tour group posing for a photo was standing on the steps of Memorial Church facing Tercentenary Theatre. When the man shot himself, the people on the steps took off running across the grass, according to Jorge A. Araya Amador ’14, who was walking by Emerson Hall at the time.

Just after 11 a.m., at least 10 officers had responded, marking off sections of the eastern half of Harvard Yard with police tape.

Cambridge Fire and Rescue pronounced the individual dead on the scene. HUPD and the Middlesex District Attorney’s office declined to provide the man’s name.

Katherine C. Mentzinger ’14, who saw the tourists from her friend’s window, said that the members of the tour group who had been near the scene of the incident were taken aside to be questioned by police. Many of the individuals were crying, she said.

“From my friend’s window, I could see him in a pool of blood,” Mentzinger said.

Thayer resident Nathaniel J. Miller ’14 said that people in his dorm were “shaken a little bit, but no one [was] too hysterical.”

The incident occurred during Yom Kippur services in Memorial Church. Service attendees who exited the church at around 12:30 p.m. said that they had not heard anything about the shooting that had occurred just a few feet outside.

Two police officers entered the church toward the beginning of services, but there was no sense of alarm or panic, said Lindsay K. Berger, a Harvard Kennedy School student who was in Memorial Church observing the holiday. Several attendees were informed of the news by Crimson reporters inquiring about the incident.

College administrators—including Dean of the College Evelynn M. Hammonds, Dean of Student Life Suzy M. Nelson, and Secretary of the Administrative Board John “Jay” L. Ellison—were on the scene throughout much of the day.

At first, police closed off only the grassy area of the yard, allowing bystanders to walk along the pathways near University Hall, Widener Library, and Sever Hall. But as the day progressed, the perimeter grew until several gates on Mass. Ave. and Quincy St. were closed and the entirety of Tercentenary Theatre was cordoned off with yellow tape.

While police stood watch over the body in Tercentenary Theatre, tour groups and pedestrians continued to pass through the other side of Harvard Yard as usual.

At some point in the afternoon, authorities removed the body, and a man with a yellow cleaning cart showed up to clean off the granite.

By 3:45 p.m., the police tape had been taken down, and tourists resumed posing and taking photographs in front of Memorial Church. A damp spot remained near the area where the man had fallen.

Sometime between Saturday and Sunday afternoon, a single bouquet of red and orange roses was placed where the body had lain. A sealed letter lay next to the bouquet with the words “To my friend” written in neat cursive on the front.

What he left behind: A 1,905-page suicide note

Author described nihilistic outlook

David Abel

Boston Globe Staff

September 27, 2010

Mitchell Heisman spent years crafting his message.

In the end, no one really knows what led Mitchell Heisman, an erudite, wry, handsome 35-year-old, to walk into Harvard Yard on the holiest day in his faith and fire one shot from a silver revolver into his right temple, on the top step of Memorial Church, where hundreds gathered to observe the Jewish Day of Atonement.

But if the 1,905-page suicide note he left is to be believed — a work he spent five years honing and that his family and others received in a posthumous e-mail after his suicide last Saturday morning on Yom Kippur — Heisman took his life as part of a philosophical exploration he called “an experiment in nihilism.’’

At the end of his note, a dense, scholarly work with 1,433 footnotes, a 20-page bibliography, and more than 1,700 references to God and 200 references to the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, Heisman sums up his experiment:

“Every word, every thought, and every emotion come back to one core problem: life is meaningless,’’ he wrote. “The experiment in nihilism is to seek out and expose every illusion and every myth, wherever it may lead, no matter what, even if it kills us.’’

Over the years, as he became more immersed in his work, often laboring over it 12 hours a day, Heisman shared bits with friends and family but never elaborated on the extent of his nihilism — his hardened view that life is vapid and nonsensical, that values are pretense, that the “unreasoned conviction in the rightness of life over death is like a god or a mass delusion.’’

He told them he was working on a history of the Norman conquest of England, cloistered in a cramped apartment he shared in Somerville. They knew the clean-shaven young man from suburban New Jersey, who always called his elderly godmother on her birthday and once donated $200 to Harvard Hillel for sponsoring services at Memorial Church, to be intensely committed to his work.

Neither his mother, sister, nor the roommates from whom he sought forgiveness in the hours before he died had any idea he was about to kill himself. They and others have been groping for answers to why he did it and in such a public way, on such a holy day.

“He was very cordial, very charming, you would never know that something was wrong,’’ said Lonni Heisman, his mother. He frequently told her he loved her, and had recently visited to help her prepare for a move. “I’m still in shock and I can’t understand how he could have hid this,’’ she said. “He had everything going for him. He was in perfect health. He was handsome, smart, a good person. I’ll never understand it.’’

She said he was a gregarious child who grew introverted after his father, an engineer, died of a heart attack when Mitchell was 12 years old. As he got older, he became increasingly bookish and went on to study psychology at the University at Albany in New York, where he seemed shy to friends and spent much of his time reading.

After college, Heisman worked at bookstores, including the Strand in Manhattan, enabling him to amass a library of thousands of books. About five years ago, he moved to Somerville to focus on writing and be near major university libraries.

He led a Spartan existence, subsisting on microwave meals, chicken wings, and energy bars, and surviving mainly on money left to him after his father’s death. He was tall, with dark eyes, and dated when he needed a break from his solitude, rarely having trouble attracting women. But he broke off the relationships quickly, saying he was too busy writing a book.

To help him concentrate, Heisman often listened to a constant loop of Bach’s “Well-Tempered Clavier,’’ which he felt synthesized the mind’s competing strains of emotion and reason, went to a gym daily, and took Ritalin, which his mother thinks may have induced depression and led to his suicide.

One of his longtime roommates, David Barnes, described Heisman as quiet and considerate, never angry. He engaged in conversation by asking questions; when he spoke he often gave deliberate, lengthy responses. “He could get intense talking about his book,’’ Barnes said. “There was definitely a lot of emotion pent up in this project.’’

Barnes and relatives said Heisman bought the gun, a .38-caliber pistol, three years ago, though they don’t know where, and they believe he had only one purpose for it: to commit suicide when he finished his book.

“He wasn’t going anywhere dangerous; he wasn’t paranoid; he wasn’t worried about anyone hurting him or breaking in,’’ Barnes said. “I couldn’t imagine him buying a gun for any other reason.’’

A month ago, as he began wrapping up his writing, he asked Barnes if he would be a witness to the signing of his will. Barnes thought it was because he cared so much about his book and wanted to ensure it would be taken care of in case something happened.

Two days before his suicide, Heisman seemed elated. He told his roommates he had finished the book. He spent the next day at the post office, buying stamps and preparing packages for friends and family, with the book on CDs.

On the morning of Yom Kippur, Heisman showered, shaved, and ate a breakfast of chicken fingers and lentils, some of which he left on the kitchen counter, something he rarely did. He put on a white tuxedo, with white shoes, a white tie, and white socks, and donned a ill-fitting trench coat, perhaps to hide the gun.Continued...

At about 10 a.m., a half-hour or so before he would commit suicide in front of a group touring Harvard, Heisman walked into Barnes’s room. He told him the white clothing was a Jewish tradition, even though he rarely practiced his religion and had given up on the concept of God. Appearing to be in a buoyant mood, he explained the significance of Yom Kippur.

“He said he wanted me to know that if he ever did anything to offend me, he apologized and hoped that I would forgive him,’’ Barnes said.

In his book, which he titled “Suicide Note’’ and scheduled to send to hundreds of people as an e-mail attachment about five hours after his death, Heisman produced an extraordinarily lengthy treatise on why life was not worth living.

With chapter titles such as “Philosophy, Cosmology, Singularity, New Jersey’’ and “How to Breed a God,’’ and citing more than a hundred authors from futurist Ray Kurzweil to the biologist E.O. Wilson, Heisman explains how his views took shape.

“The death of my father marked the beginning, or perhaps the acceleration, of a kind of moral collapse, because the total materialization of the world from matter to humans to literal subjective experience went hand in hand with a nihilistic inability to believe in the worth of any goal,’’ he wrote.

He saw his emotions as nothing more than a product of biology, as soulless as the workings of a machine, making them in essence an illusion.

“If life is truly meaningless and there is no rational basis for choosing among fundamental alternatives, then all choices are equal and there is no fundamental ground for choosing life over death,’’ he concluded.

The darkness of his views has been too much for his friends and family, many of whom have yet to read his suicide note.

“It makes me sad and angry that he didn’t care for any facet of life other than the book,’’ Barnes said.

As his sister, Laurel Heisman, spent last week sifting through what remains of his things — a poster in German, a well-made bed, piles of books in a small room shrouded with a dark curtain — she said she received a separate, posthumous note from him asking that she preserve a website he created to publish his book, a burden she has agreed to bear.

“I love you,’’ he wrote to her.

She wishes she could have made him see more of the beauty of life, and how we create our own value and give our own meaning to life. She might have taken him up a mountain or held him more closely.

“He just told us the safe things, because he knew we would have tried to stop him,’’ she said. “It’s really hard. It’s not like someone who was really depressed because they lost a lover. His whole ideology was wrapped in this concept of nihilism. I wish we could have made him see things differently.’’